To new beginnings

After being office-less for 10 days (technically 4 days not counting public holidays and weekends), many of us in the Menzies building have safely moved yesterday to our temporary offices in Building 6 while Menzies undergo renovations for the next 2+ years (anyone wanna bet it’ll take more than 2 years or not?).

My old office had a pretty nice view of the hex wall but I don’t know where it is now. Last I saw it was clearly labelled to be moved to level 3 corridors but maybe it’s yet to be moved. Impressively, they did manage to bring my big and small whiteboard as well as the large corkboard in my old office – now it just needs to be hanged and I need to figure out where the whiteboard markers are stored.

You should check out the view of the corridor from my office ;) pic.twitter.com/8L0fCf6F0P

— Emi Tanaka (田中愛美) 💉💉💉 ((statsgen?)) August 1, 2020

While that’s happening, in the weekends I saw some twitter posts (yet again) about shade against academia. The specific post was referring to the lower pay in academia and said in industry there’s no penalty in walking away from a job with bad work culture (insinuating that’s not the case in academia). Give it another week or so, I’m sure I’ll see another post against the academic culture, a #quitlit post or how great an industry position is.

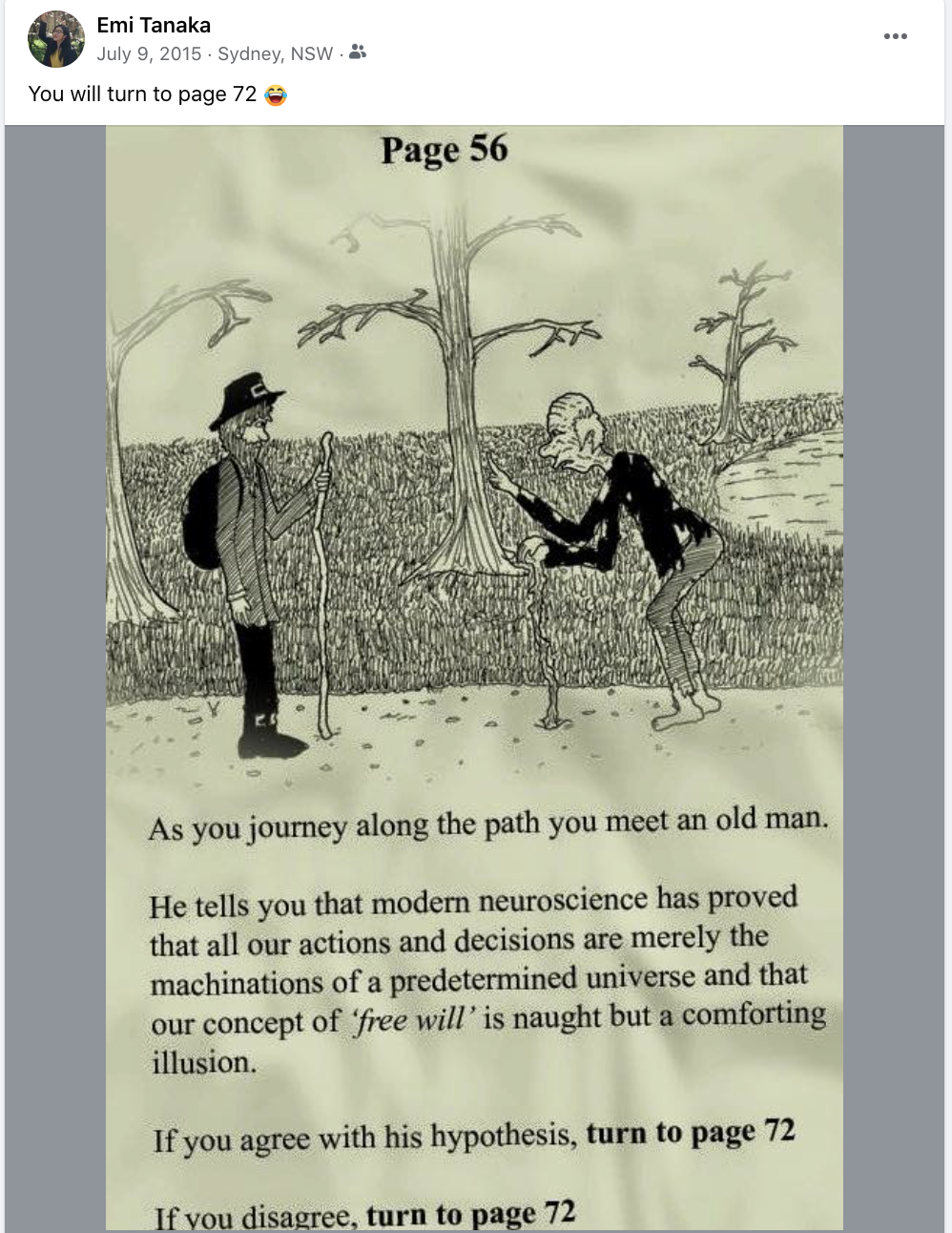

Based on the frequency you see these posts, you’d think academia is an awful place. It’s also not hard to find people who’ll affirm your belief. Then why do people stay in academia? There’s one reason I hear quite often – they get freedom. That answer always remind me of a page from this book I saw years ago – this page still makes me laugh 😂

There’s a well known experimental study by L. Festinger and Carlsmith (1959) that studied subjects that had to do repetitive, monotonous tasks and was told to lie to the next “subject” (actually a hired accomplice) that the task was interesting and enjoyable. Some subjects were paid $1 for lying while others were paid $20. There was a control group that didn’t have to lie. There were 20 subjects in each of the three groups. After the task, each subject was asked to rate (on a scale of -5 to +5 where -5 is dislike, and +5 is like) how much they enjoyed the tasks. The subjects that were paid $1 reported on average a higher level of enjoyment (1.35) than subjects who were paid $20 (-0.50); the average level of enjoyment for control group was -0.45.

The results aligned with the theory of cognitive dissonance by Leon Festinger (1957), which suggests that we have an inner drive to hold our cognitive elements (attitudes, perceptions, knowledge and beliefs) in harmony and we feel discomfort when some of these elements are inconsistent. The study by L. Festinger and Carlsmith (1959) suggested that people who were paid $1 to lie felt they had to justify the poor payment by convincing themselves that they actually enjoyed the task, while those that were paid $20 were well rewarded and did not experience cognitive dissonance.

The experimental result in L. Festinger and Carlsmith (1959) reminded me of the often touted reason where industry is better than academia: money, and the academics that give reasons of why they stay in academia, despite the lower pay. If you are an academic, did you really choose to be in academia for some higher purpose? Or do you just stay because we tend to succumb to inertia and that was the path of least resistance? I tend to be skeptical of any rosy picture that either side presents. I don’t deny though that I get affected by the strong emotions that people display against academia – more so, because I know some comments are true – academic culture and system needs to improve – but the eternal question is who’s going to champion the change? The way I see it, it’s a collective responsibility so everyone should contribute to make it a better place, with more responsibility on those in higher echelon.

Reality is complex and as any job, academic job is a mix of good, bad, joy, and tediuous. Sometimes it’s just the small acts of people around that consider your best interest at heart – see you as a person and not an expendable tool – that makes it worthwhile even if the system doesn’t work for you. I can’t say academia is bad when my colleague is considerate of me, telling me of a pathway so I can get a bigger office, and another colleague allocating himself the smaller office so a large office can be allocated to someone else (despite himself being a former head of department and a professor). There are some bad apples of course, but plenty of good people in academia.

If a workplace culture is bad or it’s not working well for you though, by all means walk away – maybe giving a reasonable chance to see if people take actions to rectify the issues first. In my relatively short career, I’ve butted heads a number of times already (concidentally all professors – yeah, I’m harder on people with power because I expect better of them) so I won’t be surprised a number of people dislike me, but also at the same time, I know there are plenty of people that appreciate me for my conduct and contributions. If anything, it’s the difficult times that can be revealing of character and bring people together. It’s always the people’s conduct that make the workplace great or not – or at least bearable.